The Grand Canal

M. Zhu

Introduction/ Background

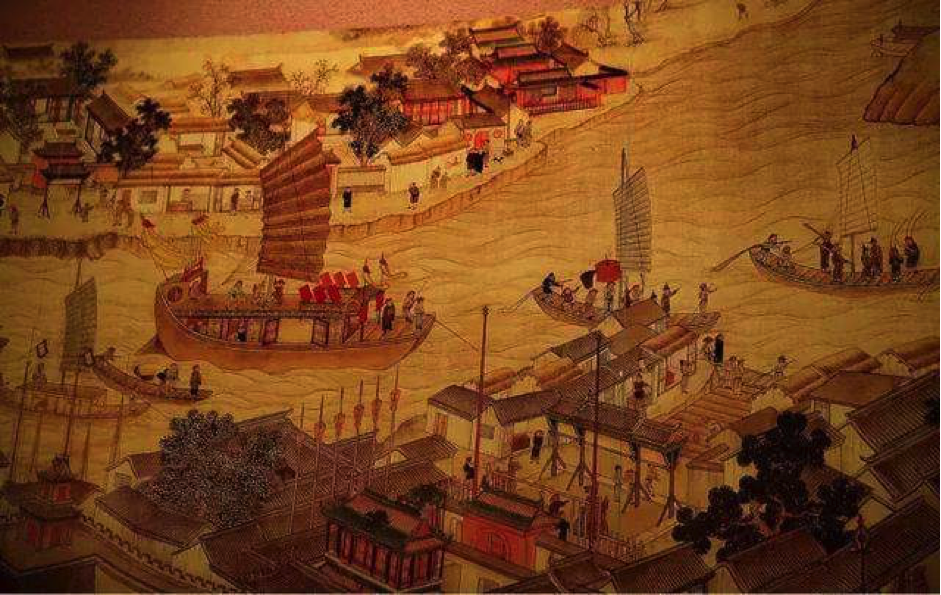

The Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal starts from Beijing in the north and reaches Hangzhou in the south and communicates with the five most important water systems in China, which is the longest artificial river made by manpower in the world.

As early as the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, a ditch was chiseled to connect the Han City (today’s Yangzhou) and Huai’an so that Yangtze River and Huai River was also connected.

During the period from the Han Dynasty to the Northern and Southern Dynasties, a number of waterways communicating the Yellow River and the Huai River were ditched. All these were the early river sections that later become converted into the Grand Canal.

During the Sui and Tang Dynasties, the “transport system of the Grand Canal centered Luoyang, and reached the Guanzhong Basin in the west, the Hebei Plain in the north, and the Taihu Lake Basin in the south, covering seven provinces including today’s Shanxi, Henan, Hebei, Anhui, Jiangsu, Shandong and Zhejiang” (Wu 2012, 112).

By Ming Dynasty, the “full line of navigation” was basically realized. In order to realize the supply of grain to the north from the south, the canal was responsible for the transportation of tons of grain per year and was a veritable lifeline for the Qing Dynasty.

Near the end of 19th century, sea transportation began to rise. Later, with the construction of the Railway from Tianjin to Pukou, the role of the Beijing-Hangzhou Canal gradually decreased.

After the diversion of the Yellow River, the water source in the river section of Shandong was insufficient, the river channel was shallow and silted into a flat land, resulting in the cutting off of the north-south transportation over the canal. Combining the complex historical background of Qing Dynasty, there existed different reasons for the decline of the Grand Canal.

Historical Significance of the Grand Canal

The construction of the canal has great significance in Chinese history.

- First of all, the connection between the north and the south helped strengthened the central governance over the whole country.

- Secondly, the adequate food and water supply from the south was delivered through the canal to the norther part of China, which often suffered from drought.

- Furthermore, the communication also promoted the cultural exchange.

- And lastly, the economy of the small towns along the river quickly emerged and prospered.

Reasons for Decline of the Grand Canal

Hydraulic Challenges in Grand Canal Maintenance

The fate of the canal has not been able to get rid of the serious constraints of the geographical environment from beginning to end. In order to save manpower and material resources, the construction of Beijing-Hangzhou Canal adopted the original natural rivers and lakes as the main body, and some of the river sections were artificially excavated. The water source in many areas of the canal was extremely poor.

In order to solve the problem of water source, the Ming Dynasty adopted the measures of leading the springs from Yuquan Mountain to flow into Huitong River to guarantee adequate water flow for transportation.

However, this not only seriously affected the irrigation system for farmland water conservancy, but also failed to solve the problem of insufficient water supply. Since the amount of groundwater is directly affected by surface precipitation, therefore, when the surface precipitation is insufficient, the underground water source is inevitably short, so the water source is extremely unstable.

In addition, affected by the fact that the terrain descends from west to east, most of the rivers flow from the west to the east (or to the southeast and northeast) into the sea. Since the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal spans from the north to the south, it is inevitable to intersect with these natural rivers.

Although the communication could offer more water resources to the canal, it seriously hindered the draining of the natural rivers to the west, thus affecting the stability of the canal. Once these rivers overflow, floods would happen in the plain areas in Hebei Province, causing the ships to sink.

In the early Qing Dynasty, water was often reduced into Hongze Lake during the flood season. The problem was silt building up in the complex of waterworks in the junction region of the Yellow and Huai Rivers, Hongze Lake, and the Grand Canal.

Until the late sixteenth century, the waterworks were managed under a theory of “dividing the channel” of the Yellow River into several smaller ones to disperse floodwaters. All that did, though, was to slow the river and increase the silting (Marks 2017, 272).

In the late Qing Dynasty, the lower reaches of the Yellow River were silted up by the sediments. During the summer and autumn flood seasons, the turbidity of the Yellow River often poured into the Hongze Lake and the canal. Not only was the shipment port blocked, but the eastern part of Hongze Lake was also silted.

The Improper Governance of the Canal

Water transportation of grain to the capital is a form of land tax in imperial China. In order to maintain the navigation of the Grand Canal, the Ming and Qing governments have implemented a lot of improvement measures for the governance of the Grand Canal. However, those methods often focused only on the transportation function of the canal but lacked an overall planning for the long-term management of the canal.For example, in the early period of Emperor Kangxi, up to 430 springs were dug up for water supply.

Although this method solved the silting problem for some time, the uncontrolled development of underground springs in a long period of time would inevitably lead to the destruction of water circulation balance, which in turn would affect the normal supply of surface water. As a result, a large amount of sediment was brought along with this way of transportation, gradually causing the whole canal to be silted up.

Moreover, when dealing with the relationship between the canal and the Yellow River, the priorities of both the Ming and Qing governments still focused on the protection of water transportation for grain. Neglecting the long-term interests of the people’s livelihood and the canal itself, the imperial rulers manually excavated branches in the lower reaches of the Yellow River to ensure the smooth transportation over the canal.

After the Mid-Tang Dynasty, China’s social and economic center has gradually moved southward. The development around the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River have become the main focus for the government’s fiscal revenue.

Both Tang and Song dynasties paid special attention to the Bian River, which almost became the lifeline for the nation’s development. However, the frequent silts in Bian River were closely related to the Yellow River.

Since the end of the Tang Dynasty, the sediment concentration of the Yellow River has increased significantly, and the shifting of the routes has continued to happen. As a result, most of the artificial canals in the Yellow River Basin did not live long except for a very small number, most of which had become land already. The large amount of sediment in the Yellow River continuously irrigated the canal rivers and lakes along its channels.

Based on the fact that it was impossible to completely shake off the threat of the Yellow River, the government should have vigorously put money and energy in the governance of the Yellow River.

In the middle period of Kangxi’s reign, the government tried very hard to cut off the connection of the canal to Yellow River. Originally, the Huai River had its own waterway to flow from the land into the ocean. However, the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River have been diverted many times, frequently making its way through Huai River to the sea. This resulted in the accumulation of sedimentation in the lower reaches of the Huai River and the poor drainage of the water.

And backward flows of the yellow water have also brought a lot of negative influence. What’s worse, the government even tried the method of leading water from the Yellow River to guarantee the amount of water of the Grand Canal, which was a short-term solution and caused irreparable loss.

Corruption in the Watercourse Administration System

The rise and fall of the canal was often closely related to the rise and fall of the political situation and social stability.

During the Yongzheng and Qianlong periods, a large number of human and material resources were put to ensure the normal operation of the canal. The transport path could remain basically unimpeded for a while.

However, in the later half of the Qianlong period, with the rise of corruption and the decline of clean politics, the political situation was quickly ruined.

Especially after the reign of Emperor Daoguang, China was invaded by outside force. And the imperial system began to collapse and China gradually became a semi-feudal and semi-colonial society.

Under the pressure of internal and external troubles, corruption in watercourse administration in the late Qing Dynasty (Jiaqing to Xianfeng period) increased day by day. River labor surged but the river defense slacked.

At that time, in order to ensure the smooth flow of the lifeline of the capital, the Qing government did not hesitate to invest huge sums of money every year to operate the canal, and the budget increased year by year. The positions in watercourse administration were very popular among officials who aimed to make a fortune through corruption.

For instance, in the period of Jiaqing, there were always three candidates for the position of governor-general for watercourse administration every year (Sun 2009, 195).

In the late Qing Dynasty, the appointment of the watercourse officials was so frequent that it reflected not only the incompetence of most of the officials at that time, but also the extreme corruption and mismanagement of the political system, which would inevitably cause serious harm to the river management project.

Those officials would think of various ways to get money from the project. Usually, they would make up many items that needed to be solved during the governance process and faked reports in which the final cost was actually four or five times more than the normal cost. Therefore, there appeared a saying among the people that “the more money, the more disasters”.

Frequently affected by the disasters in the Yellow River and the demotivation in water maintenance, the water conditions of the canal became worse and worse and dangerous situations happened frequently.

After the Opium War, with the advent of Western advanced ships, the safety of shipping was greatly increased. With the strengthening of shipping and the construction of railways, the Qing government finally gave up the canal transportation and turned to sea transportation.

Conclusion

It can be seen from the above exploration that the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal was inherently insufficient due to natural conditions at the time of excavation and was not an ideal channel.

The rulers have invested a lot of manpower and material resources to maintain the smooth flow of their transport. However, as an artificial river, the destiny of the Grand Canal is in line with the political situation and the degree of attention, demand and utilization from the government and common people.

As an important historical heritage, the protection of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal has been highly valued by Chinese government. To protect the authenticity and integrity of the canal heritage, it is necessary to fully understand the special nature and geographical attributes of the canal.

- First of all, the canal plays a role in highlighting national identity and promoting cultural identity;

- Secondly, as an important guarantee for regional urban and rural production and life, it has the value of practical functions such as water transportation, shipping and irrigation (Yu et al. 2008, 5);

- Thirdly, as the regional ecological infrastructure, it is the key pattern to ensure the ecological security of the country;

- Lastly, the canal also has the potential for the public’s leisure demand, for example, it can be used as historical materials and provides areas for exercises and scenery sites.

Only by fully understanding and handling the interrelationship among these values can we really protect and utilize the canal heritage and restore its role in the process of contemporary and future Chinese civilization.

Reference

Marks, Robert-B. 2017. China: An Environmental History. Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield.

Junya, Ma, and Tim Wright. “Sacrificing Local Interests: Water Control Policies of the Ming and Qing Governments and the Local Economy of Huaibei, 1495–1949.” Modern Asian Studies 47, no. 4 (2013): 1348–76. doi:10.1017/S0026749X12000583.

Sun, Jing-tao. 2009. “Resisting Marginalization in Late Qing China: Local Dynamics in Jining’s Initial Modern Transformation, 1881-1911”. East Asia: An International Quarterly, 26 no.3, 191-212.

Wu, Cui, and Wang Min. 2010. “The Decline of Shandong Section of Grand Canal in History.” Journal of Baicheng Normal College 24 no.1 (Feb.): 70-72.

Wu, Hai-tao. 2012. “The Occurrence of Huai River Problems and the Measures Taken by the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties.” Anhui Historiography no.4: 111-116.

Yu, Kong-jian, Li Di-hua, Li Wei. 2008. “Recognition of the Holistic Values of The Grand Canal.” Progress in Geography 27 no.2 (Mar.): 1-9.